My parents liked to joke that theirs was a “mixed marriage” because she was a Russlander Mennonite and he was a Kanadier Mennonite.

It was only funny to that tiny subset of the population who was both in the community enough to know the difference and out of the community enough to think it a laughing matter.

My mother, herself, wouldn’t have understood the joke until after she was married. When she met my father, she knew only that he was Mennonite; she had no inkling of all the various types of Mennonites out there with different names and practices. She was startled when he wrote Bergthal Mennonite beside his name in the marriage register.

(It is my opinion that all courting Mennonite couples should discuss their respective schismatic histories with their prospective partners before embarking on marriage. If only to prevent the spread of Schismatically Transmitted Inferences. But I wasn’t around to give them advice back in 1958 and they, admittedly, managed well enough without it).

But of course my father didn’t identify himself as Kanadier in the marriage register. That wasn’t the name of his Church. It was the nickname of his people — the people who migrated to Canada about 50 years before my mother’s people.

I don’t imagine that he used the term with her when they met while he was visiting Ontario. “Kanadier” and “Russlander” were not derogatory labels. But neither were they not derogatory.

Because everyone who knew anything about it also knew that the Russlanders (who came to Canada in the 1920s) were snobs and Kanadiers (who came in the 1870s) were hicks. Or rather, it was generally agreed upon among the Kanadier that Russlanders thought that the Kanadier were uneducated, fun-despising simpletons and it was generally agreed upon among the Russlander that the Kanadier thought the Russlanders were arrogant, worldly know-it-alls.

Not that they would ever have said it quite like that.

The Kanadiers would have said it in Plautdietsch.

And the Russlanders would have said it by suggesting reforms. Like, say, a reform to get rid of Plautdietsch.

The theory has it that the greatest class conflict in all of Mennonite history was fought over the right to speak Plautdietsch.

As class conflicts go, one has to admit that it was remarkably undramatic.

Marx would have been ashamed.

Where were the avaricious bourgeoisie exploiting the labour of the disgruntled proletarians? And where the inevitable revolution?

Back in Russia, sure. That’s where.

There, we had a couple of factory owners in our number who could rightly be considered bourgeoisie and also a few Mennonites with large enough estates to afford them some aristocratic airs. But out of 20,000 Russlander Mennonites, very few of them had been factory owners and aristocrats. My maternal family boasts such elite occupations as Town Clerk on one side and the disabled old man that the village supported on the other.

And the Kanadier don’t really fit Marx’s definition of the proletariat, either. Not only did my father’s family own their own farms, they also had a cow or two and thus had control of the means of the production of schmauntfat. And what more could they want?

Well, I guess they wanted Plautdietsch.

According to the Kanadier Mennonites of my acquaintance, the Russlander rejected Plautdietsch out of elitism, wrinkling their noses at the sound of it. Apparently, the Russlander arrived in North America and had barely finished brushing the dust off their travelling clothes when they began their concerted attack on the language of the Mennonites who had come before them, finding it crude and unrefined.

I should have doubted this story from the assertion of any Mennonites ever acting together in concert. Instead, I asked my mother.

In fact, I interrogated her relentlessly.

I learned that it was true that she did not learn Plautdietsch as a child but she insisted that this was not because of elitism. In her family, she claimed, Plautdietsch was seen as an “adult language.”

Was that because it was seen as coarse? I asked.

She denied this.

Because it wasn’t a “proper” language?

No.

Because it was R-Rated in some way?

No. No. No.

Of course, by the time I was grilling her, my mother was already fully aware that the Kanadiers thought her ignorance of Plautdietsch was a mark of elitism. And some might argue that she protested too much in an effort to deny the classicism of her people.

But I am inclined to believe her.

According to my mother, her parents had thought that my mother and her brothers would simply pick up Plautdietsch on their own as they grew older, as they themselves had done in Russia. It worked for the boys, who happened to have friends who spoke Plautdietsch at home. But it didn’t work for my mother. She said that she just left home too early.

Searching through the reams of historical scholarship on the matter, I find that my grandparents brought their attitudes towards Plautdietsch with them from Russia. According to James Urry, Mennonites in the Molotschna Colony turned away from Plautdietsch in the late nineteenth century but the Mennonites from Chortitza were more lackadaisical about their policing of language. The Kandadier Mennonites, coming to Canada before the major shifts in language and also largely (but not entirely) from Chortitza colonies, held onto Plautdietsch.

Ironically, my father’s Kanadier family boasts a bit of Molotschna heritage and my mother’s Russlander family has none, only Chortitza. Which could explain things.

Nonetheless, when my mother moved with my father to Altona, Manitoba, she learned that she was a Russlander and therefore a snob.

She learned quickly not to speak German to the people she met casually in Altona. She knew High German as her mother tongue but the Plautdietsch Kanadier would see her as taking on airs if she spoke it and so she stuck to English with strangers and let them believe that she couldn’t understand the words they spoke confidentially among themselves.

Such were the travails of an unwitting pawn in a Mennonite class conflict.

But a generation and a bit later, the conflict is all but forgotten. And that is not because of a Mennonite propensity to bury conflict. Oh, no. We have kept conflicts over the proper mode of baptism going for longer than this one. And don’t get me started about the Flemish and the Frisian dispute.

Clearly, if we had wanted to, we could have kept this conflict alive. But I think that for all the casting of aspersions at each other, there was also a fascination between the groups.

My parents were not the only young lovers to cross the Russlander-Kanadier divide. Whenever I am talking to my older friends and relatives who still feel this conflict in their bones, I eventually ask them: If the conflict was so deep, why did so many Russlander and Kanadier marry each other?

This usually ends the conversation as they drift off into a reverie counting up all the couples they know or knew who had safely navigated the treacherous waters of a mixed Mennonite union.

And I take the time this affords me to mix up another round of cocktails.

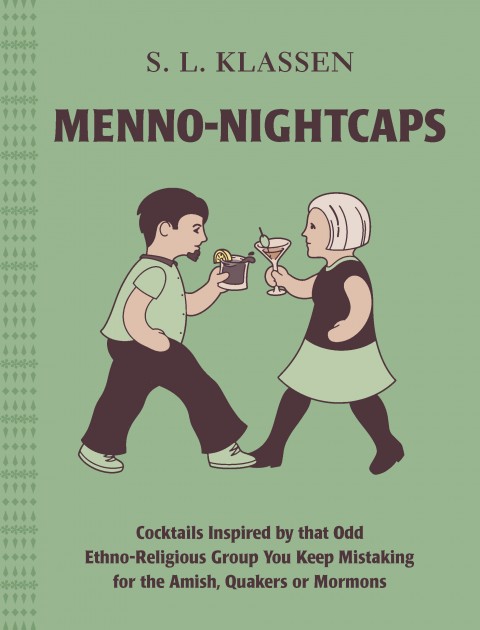

In my forthcoming Mennonite cocktail book (Touchwood Editions, 2021), I will have a cocktail called “Plautdietsch Punch” in honour of the language. Here, I present instead a cocktail that honours the conflict between the Russlanders and the Kanadiers. In the interests of harmony, I have chosen a cocktail that can be made with either Russian vodka or Canadian whiskey. Go ahead and make one of each and see if they get along.

A Question of Class

- 1 oz vodka or whiskey

- 1 oz lemon juice

- 1 oz Chambord or other raspberry liqueur.

Combine ingredients in a cocktail shaker with ice. Shake thoroughly. Strain into a coupe glass. Garnish with frozen raspberries and/or lemon rind, recognizing that lemon peel makes one drink no better or worse than the other.

You always tickle my funny bone. I wonder how old you are. I am 75. From Homewood, Mb

I did reply. At length. Readers have been spared my vitriol has disappeared.

This was so interesting. My mother use to talk about all the crazy splits in the Whisler Mennonite in Indiana.I met German speaking, Mennonites, dairy farmers in Uruguay. The migrated in the 1940s to escape Hitler. Back when I was young on the family produce farm. My father was an eccentric. He built a still to cook our spoiled produce. The feds ATF called and threatened to blow up his still. The feds ended up sending him a spirits licence. I use to put red raspberries in either vodka or gin and allow it to marinate. My Italian friends loved it.

You have done it again Sherri.

I chuckled throughout the reading as you captured the essence of the Russlander Kanadier class struggles.

I just counted and there were 6 Russlander and Kanadier marriages in our family and they seemed on the surface at least to be happy. Whether there was any rivalry in establishing who was superior, only the couples can tell.

My mother, whose family was from Prussia and spoke high German always thought the Schweitzer dialect that my father spoke was not at all proper German, and she was not shy about saying so. Reading this made me laugh as I didn’t realize the humble Mennonites paid so much attention to class differentiations.

I also love your cocktail for this post…the vodka version is very close to a French martini. Now if only there were French Mennonites, we could really talk about elitism!

Oh, they moved to Altona?

well that explains the backwards yantseide attitude!

My grandfather, a Russlander, and my grandmother, a Kanadier, were the first “mixed marriage” in Steinbach and they took it as a point of PRIDE!

And for sure, plautdeistche was spoken so the little kids would not understand the adult conversation. By both my grandparents and my parents. My mom was another Russlander who married a Kanadier. Mom spoke 7 languages including high and low german.

LOL, my thoughts exactly: Oh, they moved to Altona?

well that explains the backwards yantseide attitude!

I had the same experience as your mother and never became fluent in Plautdietsch. And I always spoke “high” German with your grandmother. Except towards to the end of her life, she began to speak to me in Plautdietsch. Initially, it felt awkward, but then I thought, I should be honored. Now that I am married with children, I am considered grown-up and should converse in the grown-up language.